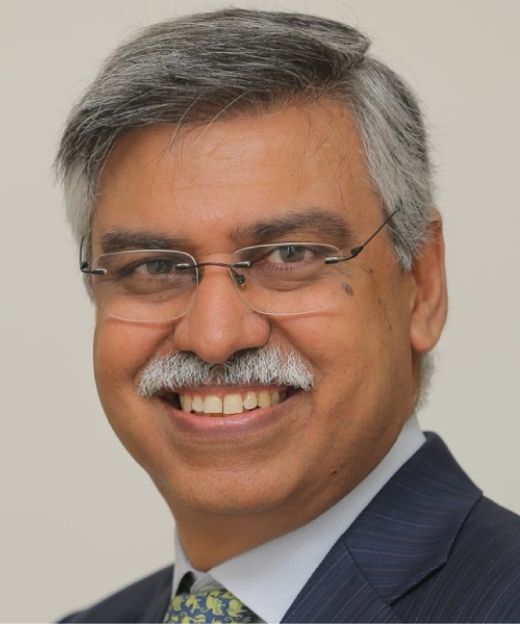

Serendipity Is Changing How People View the Arts: Sunil Kant Munjal

As Serendipity Arts Festival marked its largest ever edition, Sunil Kant Munjal, Founder and Patron looks back at the journey of the festival.

By Suman Tarafdar

India’s largest multi-disciplinary festival turns a decade old this year. Right since its first edition, it has captured the ethos of arts under a single platform in India as never before. In its breath of vision and its expanse of the arts – music, theatre, photography, public art, dance, craft, visual and culinary arts – the nation has seen nothing like this. Unsurprisingly, it has required a visionary to imagine this remarkable dream – and translate it to reality.

Sunil Kant Munjal, Founder and Patron, Serendipity Arts, is of course unique among Indian entrepreneurs in ensuring that Serendipity Arts Festival is now a benchmark setting festival, not just in India, but globally.

As SAF marks its largest ever edition, he talks to SOH about the journey of the festival. Excerpts from an interview.

The River Raga – an hour long cruise on the Mandovi with a live musical performance, has been arguably the most popular feature of the festival.

The musical performances at the end of each day provide a rousing end to each day of the festival.

Congratulations on the remarkable journey of Serendipity. What were the highlights of the 10th edition?

The 10th edition of Serendipity Arts Festival was a celebration of scale and intent. We presented over 200 multidisciplinary projects led by 42 curators – our largest edition so far. What makes this milestone distinctive is that the festival has travelled through the year: Birmingham, Ahmedabad, Delhi, Varanasi, Chennai, Gurugram, Dubai and soon Paris, before culminating in Goa. Serendipity has grown from an annual festival into an ongoing cultural ecosystem. We are also expanding our heritage activation work and unveiling among our most ambitious commissions, pushing what multidisciplinary arts can do in India.

In what ways was this the most ambitious version of the festival?

This year, we presented over 150 multidisciplinary projects across visual arts, music, dance, theatre, culinary arts, craft, photography and more. Meanwhile, we greatly expanded our programmes for children and accessibility to ensure that people of all ages and abilities can take part fully. The ambition is as much about scope as scale. For the first time, we have activated cities in India and abroad through the year, while in Goa we work across multiple heritage and public venues that demand restoration, technical rigour, and community engagement.

Our apprenticeship programmes have grown, and partnerships with institutions, heritage bodies, conservation experts, and like-minded brands now enable projects that would otherwise be impossible. Keeping the festival primarily free at this scale is itself an ambitious commitment – made possible only through careful resource management and long-term patronage.

From when it started, what have been some of the most significant learnings?

Our core learning is that a sustainable arts ecosystem needs year-round work, not just an annual festival. Starting in 2016 as a multidisciplinary platform, we quickly realised we also had to commission new work, support research, and address gaps in arts education and access. Each edition has taught us resilience – whether during the pandemic, sudden venue losses, technical failures, or extreme weather. These moments have pushed us to build stronger systems and think more inventively.

We have learned that accessibility goes beyond free entry: it means multiple languages, familiar locations, and creating conditions where a first-time visitor feels invited, not intimidated. Our long engagement with heritage sites has shown that, overseen with care, they can become living cultural spaces, not just monuments. We now know that artistic integrity and accessibility can reinforce each other – provided there is strong curation, robust public programming and genuine dialogue between artists and audiences.

What have been some of the most significant challenges in hosting the country's largest interdisciplinary festival?

The challenges are multidimensional. Programming eight disciplines at once, each with distinct artistic and technical demands, requires year-round planning and deeply collaborative teams. Balancing ambitious, uncompromising work with full accessibility means financial sustainability is always a live question. We depend on careful resource management and partners who genuinely share our values. Operationally, transforming multiple venues in Goa – especially public and heritage spaces – into sites for contemporary practice is complex and specialised. We have had to build in-house expertise in everything from heritage restoration to digital and technical infrastructure.

The subtler challenge is cultivating awareness and appreciation for multidisciplinary contemporary arts where this is not yet mainstream. We respond by creating strong curatorial contexts, demystifying work through public programming, and designing multiple entry points for different audiences. Finally, we have had to become highly resilient. The pandemic and on-ground disruptions have taught us to adapt quickly, work digitally when needed, and rebuild when plans change overnight.

The remarkable 10-year journey of SAF is above all a vision of the Sunil Kant Munjal.

What has the feedback for the festival been like? What aspects have most appreciation, what do regulars want to see more of?

The feedback has been both generous and increasingly nuanced. Audiences consistently value the festival’s accessibility and its multidisciplinary character – the chance to encounter visual arts, music, theatre, dance, culinary arts, and craft in conversation rather than isolation. Our activation of heritage spaces has gone down particularly well. People respond strongly to seeing historic buildings restored and re-energised through contemporary art, connecting memory and the present. Community programmes – particularly school engagements and apprenticeships – continue to draw meaningful responses. Watching children and young practitioners engage with confidence tells us we are helping shape future cultural citizens. Culinary programming also resonates deeply with local communities as it honours regional food traditions while exploring their evolution.

Regulars ask for more boundary-pushing commissions, more direct encounters with artists, and deeper explorations of how traditional practices can be reimagined in contemporary forms. Craft collaborations between master artisans and designers are in especially high demand. The reception to our Birmingham intervention has confirmed that this model travels – and that there is appetite for Serendipity-like ecosystems in other cities.

Personally, for you what have been some of the most satisfactory achievements of the festival? What would you like people to note most about the festival?

For me, the deepest satisfaction is seeing Serendipity evolve from a vision into a living ecosystem that changes how communities meet contemporary art. Moments like school children discovering installations with delight, apprentices growing into independent practitioners, or craftspeople finding new visibility and livelihoods through collaboration stay with me. Projects such as Talatum (our reimagining of The Tempest in a circus tent in 2016) or Amitesh Grover’s The Money Opera (2022), which turned an abandoned building into immersive theatre, have been especially rewarding because of how intensely audiences engaged with them.

Our heritage work is another key achievement: we are not just conserving architecture but converting it into shared cultural spaces. If there is one thing I would like people to remember, it is that Serendipity is about access and dialogue. It breaks silos between art forms, between tradition and the contemporary, between artists and audiences, and between the local and the global. It argues that art should sit at the heart of civic life, not at its margins.

Where is the festival headed from here?

Serendipity is evolving from an annual festival into a year-round, multi-city platform, with Goa as its anchor. We are exploring how our ethos can respond to cities like Delhi, Dubai, Paris, Chennai, and Gurugram, always starting from local cultural realities rather than simply replicating the Goa edition. For each intervention, we ask: what gaps can we address, which communities can we serve, and what meaningful artistic exchanges can we enable?

We are doubling down on commissioning new work, supporting artistic research, and strengthening apprenticeship pathways. Growth for us must be strategic and sustainable – artistically, financially, and organisationally. Every new city teaches us something about what Serendipity can be. Our long-term goal is constant: an ecosystem where crafts persons are visible stakeholders, art is part of everyday life, education nurtures both livelihood and imagination, and one where the arts are central to civic wellbeing.

For you, what else has been most significant about the festival?

Serendipity Arts Festival embodies a distinct model of cultural patronage in India – one that honours historical traditions of supporting the arts while meeting contemporary needs for inclusion and access. We have shown that it is possible to maintain high artistic standards and yet keep the work open to all. When managed carefully, artistic integrity and accessibility strengthen each other. Our multidisciplinary approach generates richer experiences and unexpected crossings: when visual arts, performance, culinary practice, and craft coexist, they trigger conversations and innovations that would not emerge in isolation. The festival’s ability to adapt – through the pandemic, logistical challenges, and setbacks – has hardened its foundations and made resilience part of its identity.

Most importantly, Serendipity is slowly shifting how people see the arts: not as elite or distant, but as everyone’s shared space, as a way of seeing the world, and as a viable field of work. It offers a model from India that can speak globally – rooted in heritage, open to experimentation, serving local communities while engaging in international dialogue.

Food has been a focus area for the festival, offering many fascinating, innovative experiences.