A Festival Where Ideas Take Flight

Celebrating its 10th edition, the Serendipity Arts Festival has transformed Goa into a global stage for art, culture, and ideas. Founder Sunil Kant Munjal speaks with SOH about building a festival of this scale and now expanding it beyond India’s shores.

By Deepali Nandwani

Serendipity Art Festival is perhaps the world's, and not just India’s, largest multidisciplinary festival, where art coalesces with theatre, culinary arts enter into conversations about heritage, preservation and dystopic futures, where dance and music strike a chord that’s way beyond ephemeral, and where projects such as Barge, Goa is a Bebinca, and What does loss taste like? spark dialogues around food, memory, traditions and the coastal communities in ways that are part humorous, part thoughtful, and part spectacle.

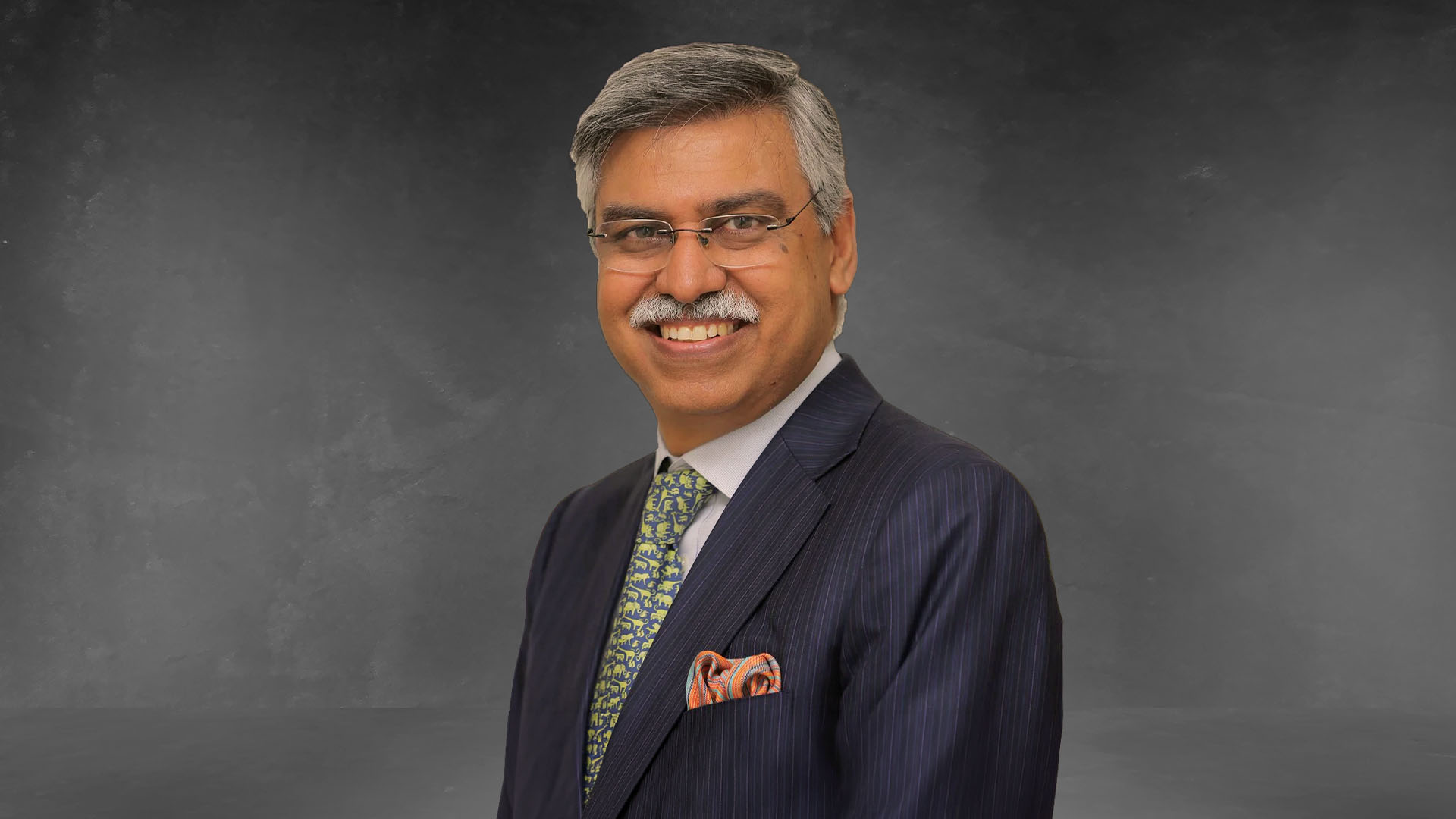

At the heart of this ambitious cultural ecosystem is the Serendipity Arts Foundation, helmed by Sunil Kant Munjal, Chairman, Hero Enterprises, though one who rarely foregrounds that identity. Munjal’s vision was rooted not in spectacle, but in reviving and democratising patronage of the arts in India—restoring access, encouraging dialogue across disciplines, and returning art to the public realm.

The unassuming and articulate founder of Serendipity Arts Festival reflects on why Goa became Serendipity’s home, how art festivals are reshaping cultural travel for discerning audiences, and why Serendipity is increasingly designed to travel—beyond Goa and beyond India.

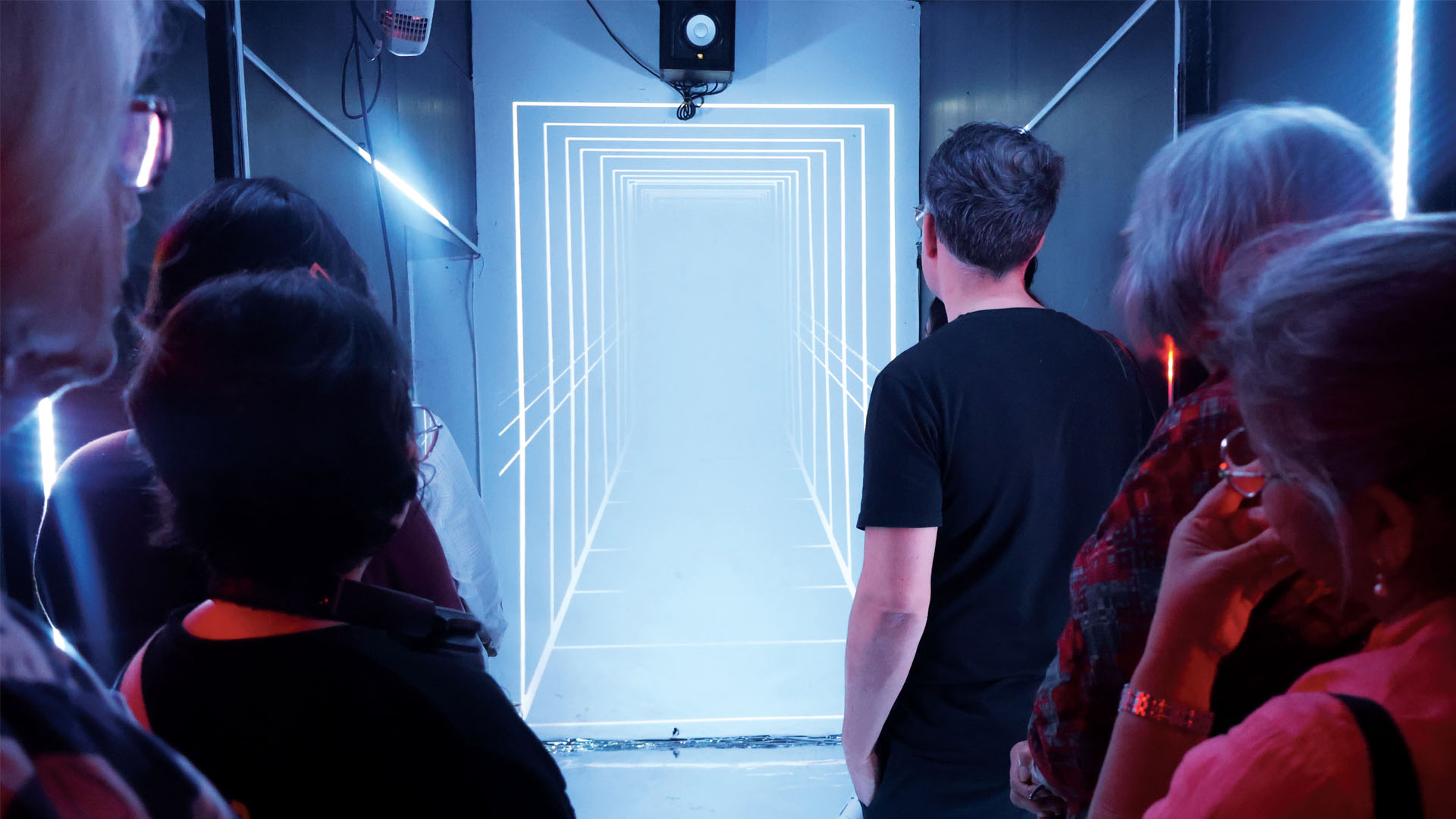

The Legends of Khasak, curated by Anuradha Kapur, reimagined at SAG Ground.

What has the 10th edition of the Serendipity Arts Festival been like?

Quite busy, actually. Overall, the response has been very good. However, several people missed attending the festival due to the recent flight disruptions. While attendance from locals and visitors from other parts of India has remained steady, I personally received 50–60 messages from overseas travellers—and I assume not everyone who faced difficulties reached out to me.

How have the locals—the Goans—responded to Serendipity?

Goans seem to have embraced the festival as their own, which, to me, is the most satisfying part. It has truly become a people’s festival. Acknowledging Goa as our host and the government as our partner, we focus heavily on Goan culture, crafts, and cuisine.

I attend the festival every year, and I’ve noticed a marked increase in coverage of Goa this year.

Coverage naturally varies each year, and depending on individual interests, you tend to notice more of what you spend time around. We’ve consistently featured street theatre, including Konkani performances, and projects on Feni and various local spices. In the past two years, we’ve highlighted Goan culture at the Art Park and explored the diverse genetic strains of people who have historically lived in Goa.

We’ve also showcased Goan cuisine in depth, bringing together Saraswat Brahmin dishes, Muslim specialties, and Christian foods from early and later communities. We believe it’s both fascinating and valuable for current generations to understand their history. Yet, the festival is not solely Goan; it’s a festival in Goa, and not even just an Indian one—we feature artists and projects from many countries.

You have now taken the festival overseas too.

We’ve been to Birmingham, Dubai, and Paris. We’ve also been to Ahmedabad, Chennai, Varanasi, and Delhi, apart from being here in Goa. The festival is being designed to travel in the future. This year is special because it’s our 10th year, so we’re doing a little bit of extra celebration.

A moment from The Legends of Khasak.

Sakuntalam, curated by Quasar Thakore Padamsee and Sankar Venkateswaran, staged at Serendipity Arts Festival 2024.

How does the character of the festival change when parts of it travel internationally?

Wherever the festival travels, we are mindful of the ecosystem. What remains consistent, however, is our core messaging on values: civic responsibility, sustainability, and relationships. These values transcend time and geography. We convey them through entertainment, culture, art, theatre, and music. Music, in particular, is universal—even percussion, as when we had 17 percussionists in Connaught Place, Delhi, each playing instruments from different parts of India. Through this, we celebrate both uniqueness and commonality.

What made you choose Goa as a destination for Serendipity?

We chose Goa because it has always had an inclusive, eclectic culture, and it has evolved dramatically over the years. Many creative people have settled here, and some of India’s best eateries—bakers, gelato makers, and not just conventional restaurants—have opened in the state.

India does have a few cities where something like this could work—Delhi, Mumbai, Hyderabad, Bengaluru—but most are primarily business destinations. When people travel there, their minds are often elsewhere. Goa, by contrast, has a culture of relaxation—people come to do nothing, unwind, or simply have fun. That mental openness makes them far more receptive to art, theatre, music, and culture, and that was really the reason.

December made sense as it is peak tourism season, enabling us to engage both locals and visitors. We never imagined people would plan their calendars around Serendipity, but they do now—and that has been transformative for Goa’s economy and ecosystem. Hotels and restaurants have certainly benefited.

When did you and your team first feel the need for something like Serendipity? And when you compare the first two or three editions with today’s world-class programming, how would you describe the scale of that evolution?

The idea of engaging with the arts predates Serendipity by many years. I set up my first performing arts foundation in 1999 in Ludhiana, and even today, it is still functioning and remains one of the most active performing arts foundations in the country. That was really the trigger.

Ludhiana, of course, is an unusual destination for a performing arts foundation. The motivation was simple: the city had no sustained cultural activity. There was business and agriculture, but this kind of cultural engagement was missing. That’s how the platform came into being. Later, when I moved to Delhi, friends began asking why I was doing high-quality performances and shows in Ludhiana and not in Delhi. My response was always the same: Delhi is a big city. It already has theatres, shows, galleries, and festivals—so why do more of the same here?

When we began thinking about Serendipity, I realised two things were missing. First, access to the arts had become extremely limited and increasingly exclusive—a global phenomenon, not just an Indian one. Second, the way art forms were being appreciated had become largely Western in approach. Traditionally in India, art forms didn’t exist in silos. Theatre, music, and dance were viewed or practised together and experienced together. We wanted to experiment with returning to that idea.

We also wanted to open up access to the arts for a much larger audience. As I built a personal art collection over time, I kept asking myself: how do you create access without inviting people into your home? The answer was to create a public space where people could come and appreciate art.

An unusual aspect of Serendipity is looking at food as a culinary art. How did that thought evolve?

Can you think of a single Indian festival or a single milestone in a family’s life that isn’t linked to food? During Eid, you share sevaiyan. Aloo puri marks one festival, halwa is offered at another prayer. And because our arts are rooted in our culture, they grow from the same source. We felt it was important to celebrate food, to heighten its awareness and visibility to the same level as any other art form.

Take what we did with Italian artist Caravaggio's painting, The Magdalen in Ecstasy. We displayed a 15th-century artwork in a 17th-century non-museum building, surrounded completely by contemporary art and in an island of complete darkness with light focused only on the artwork.

The culinary arts are approached in exactly the same way. Each project is conceived thoughtfully and meaningfully. If someone wants to skim through, they can simply have fun. But if you choose to engage deeply, you’ll discover layer upon layer in every single project.

Sunil Kant Munjal with Goa CM Pramod Sawant.

Masked performers weaved through bamboo poles on Caranzalem Beach during the 2024 edition.

Senior artists who typically engage only with commercial projects come here because they believe in what Serendipity stands for. They see it as a cultural institution with a heart, not a commercial enterprise.

Sunil Kant Munjal

Founder Patron, Serendipity Arts Foundation

How did you come to name the festival, Serendipity?

My wife used to run a bookstore called Serendipity Arts and Books at The Claridges Hotel in Delhi. When the hotel shut down for a two-year renovation, she closed the bookstore but retained the name. So when we began thinking about the festival, she suggested we call it Serendipity—because what we hope to create are happy accidents everywhere you go. With 260 projects and 650 performances, it’s impossible to see everything, even if you spend 100 days here. But serendipitously, you may encounter things that make you think. At its core, it’s about life and the journey of discovery. We’re trying to create a microcosm of that experience in a way that is interesting, engaging, experiential, and great fun. We want people to come with families, with friends, or by themselves. We are not positioning ourselves as a neutral platform, and we are certainly not preaching.

What role do you think festivals such as Serendipity or the Kochi Biennale play in shaping culture as part of travel, especially in relation to high-end tourism?

Tourism has evolved from simply visiting a site to exploring a city, and now to seeking experiences. It’s a global shift, visible at every level. What we’ve attempted is a combination of all three. The festival stands on its own, but it is also deeply woven into the fabric of the city—whether it was the night market last year, or the river cruise and the Barge this year.

These experiences draw in many people who are not regular visitors to art events or exhibitions. They hear about it, or come across it online, and sense that something distinctive is happening. And then they choose to experience it fully—bringing their children, coming with school friends, or exploring together. The result is a remarkably diverse mix of visitors. At times, simply standing at a venue and watching people pass by becomes an experience in itself—much like sitting at a café in Italy or France, observing the street. It offers the same quiet, immersive pleasure.

Looking back, what’s the single most important metric of success for you—artist engagement, programming, or community impact?

For me, it’s relationships and continuity. We don’t believe in one-offs; we prefer initiatives that grow over time. This year alone, we have 35 curators, and over the years, 62 have worked with us. We remain in touch with all of them, as well as with thousands of artists—5,000 of whom are physically present at the festival right now. That network is our biggest asset.

Many initiatives operate as islands of excellence; we’re trying to build something sustained. Our long-term projects reflect that—whether it is Young Subcontinent, which brings together artists from Afghanistan to Myanmar, or Goa Familia, which traces Goan histories through photographs, objects, and stories.

Senior artists who typically engage only with commercial projects come here because they believe in what Serendipity stands for. They see it as a cultural institution with a heart, not a commercial enterprise. Today, every major artist makes time for us. Even if we don’t know them personally, they know Serendipity—and we’re never refused a conversation.

Can you tell us about The Brij Incubator that you have set up?

The Brij in Delhi, which we are building, will house multiple institutions, including Serendipity Arts Festival. We’re launching several even before the building is complete. One is The Brij Incubator, focused on startups in arts, crafts, and culture. The rest is the stuff of another conversation.