Journeys without Itineraries

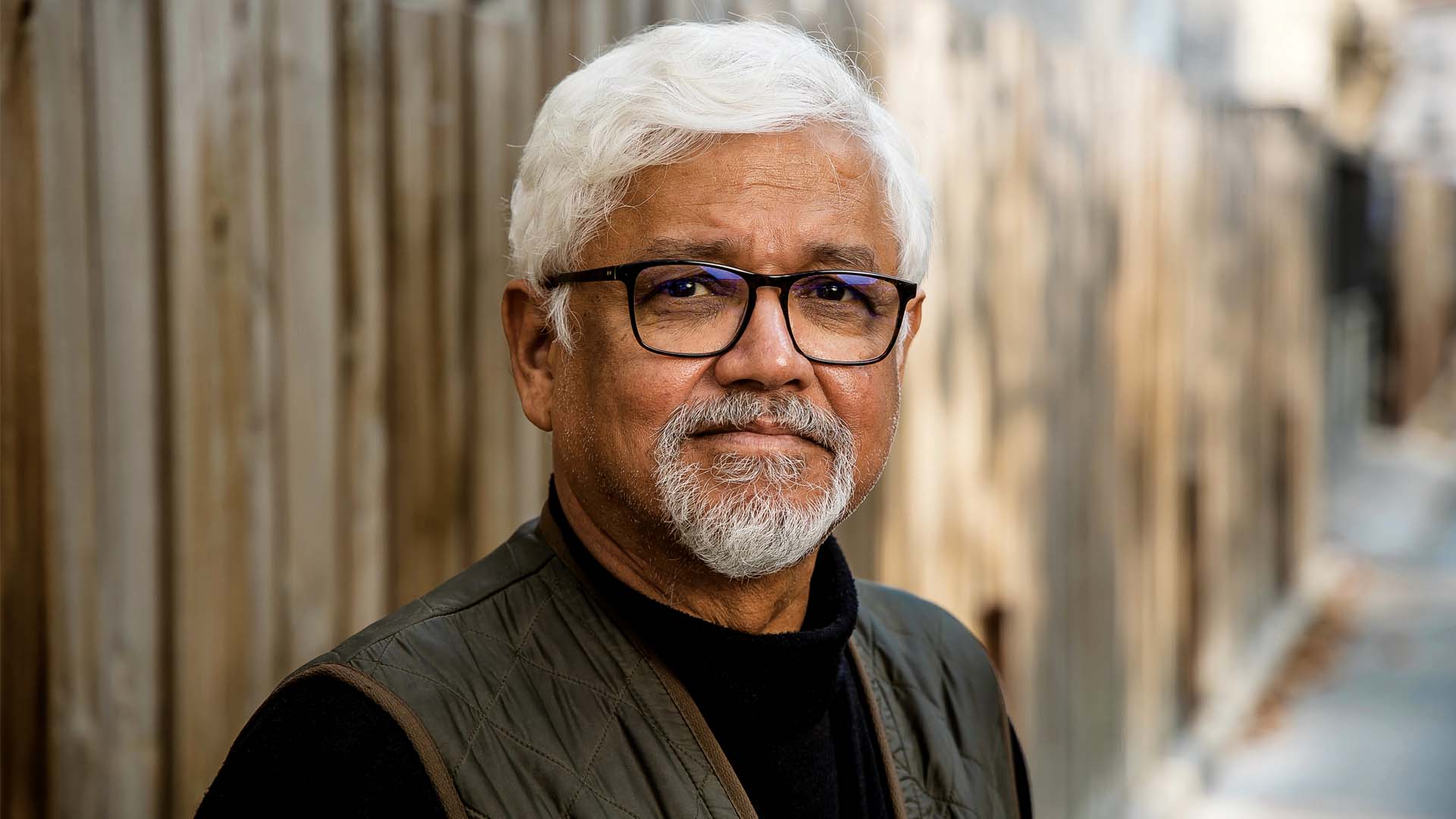

In author and Jnanpith Award Winner Amitav Ghosh’s world, travel is never an act of leisure but a condition of history. Movement—across oceans, borders and climates—becomes a way of understanding power, loss and survival.

By Deepali Nandwani

In the books of Amitav Ghosh, travel is never indulgence. It is a necessity, rupture, reckoning. People move not to collect places, but because history, trade, climate and power leave them little choice. Oceans are crossed not for leisure but for survival; borders are negotiated not with visas but with memory and loss. To travel, in Ghosh’s universe, is to recognise that movement has always been the quiet architect of the modern world.

This understanding is not merely literary. It is rooted in a life spent moving—between Calcutta and Cairo, Goa and Brooklyn, the Sundarbans and Venice, the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean. Ghosh’s journeys are never incidental to his writing; they are its foundation. He travels the way an anthropologist, a sailor and a historian might—slowly, attentively, alert to the stories embedded in land and water.

Long before airlines sold distance as aspiration, Ghosh reminds us that the Indian Ocean was already a living map, dense with exchange, migration and encounter. In the Ibis Trilogy, ships become floating worlds, carrying indentured labourers, traders, lascars and exiles across colonial trade routes that once connected India, China, Africa and Europe. These journeys are not romantic. They are shaped by coercion, reinvention and survival.

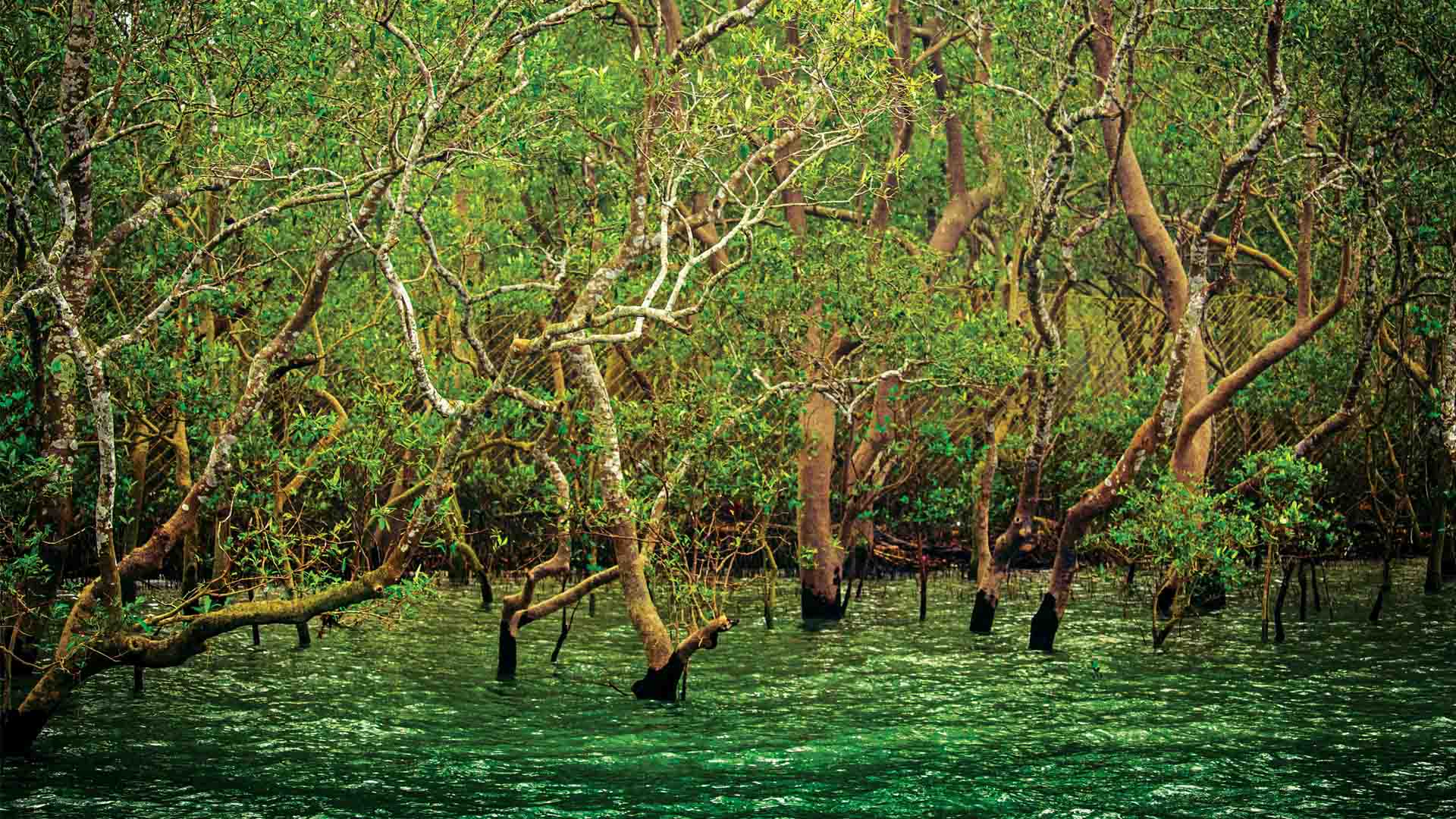

In The Shadow Lines, travel between Calcutta, London, and Dhaka reveals how invisible political boundaries can wound more deeply than physical distance. That unease deepens in The Hungry Tide, in which movement is dictated not by human desire but by tides, storms and wildlife. Across Gun Island and The Great Derangement, travel turns existential. From Bengal to Los Angeles to Venice, the question is no longer where we want to go, but whether we will be able to go at all.

Travel, Ghosh suggests, is not a transaction—but a relationship, with place, with people, and with a planet under strain. To move through the world is to inherit its histories, its inequalities, and increasingly, its ecological limits.

Venice, a city Ghosh has walked end to end—loved, understood, and worried over as waters rise.

The Sundarbans, where shifting tides and fragile land shaped The Hungry Tide’s understanding of survival.

Memories of a travelling childhood

That worldview can be traced back to early childhood. Amitav Ghosh’s life was shaped by constant movement. The son of a diplomat, he grew up across India, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, absorbing geographies and histories long before he began to write about them. Educated at The Doon School in Uttarakhand, he was a contemporary of Vikram Seth—an early crossing of paths that would later feel quietly prescient.

After choosing to study cultural anthropology at Oxford University and then becoming a writer, Ghosh travelled extensively. Reflecting on these journeys, he has said: “These travel encounters enriched my narratives in several ways. First, they gave me a deep appreciation for the beauty and diversity of the region. Second, they helped me understand the complex history of the region, including the history of colonialism and indentured labour. Third, they gave me a sense of the human cost of globalisation.”

These insights feel particularly resonant at a moment when luxury travel is undergoing a quiet recalibration. “The pursuit of speed, scale and spectacle is giving way to something more measured—journeys rooted in meaning, memory and responsibility.” As Ghosh’s worldview suggests, “The most meaningful journeys today are not about how far we travel, but how deeply we engage.”

Brooklyn and Goa are conducive to writing, reflection, and sustained attention.

Destinations that shape his narrative

Goa and Brooklyn are the two places where Ghosh feels most at ease. He splits his time between them, finding Goa congenial for writing and reflection, and Brooklyn a base for his broader intellectual life. Calcutta, however, remains central. “Calcutta remains my emotional axis,” he says—both birthplace and enduring reference point.

Egypt represents his intellectual awakening. During his early academic career, Ghosh lived and conducted fieldwork in a village near Beheira, where he studied rural life and absorbed local cultures. These experiences shaped his ethnographic sensibility and directly influenced In an Antique Land. “What drew me to Egypt in 1980 was a kind of xenophilia, a desire to embrace the globe in my own fashion, a wish to eavesdrop on an ancient civilisational conversation.”

Venice, too, occupies a special place in his imagination. In interviews around Gun Island, Ghosh has spoken of his deep attachment to the city and its waterways, as well as its vulnerability to climate change. “I have walked all of Venice, understood it, worried about it,” he says—words that capture both intimacy and foreboding.

Among his most memorable journeys is his passage through the Tenasserim Archipelago, off the coast of present-day Myanmar and Thailand. Sailing through these remote Indian Ocean waters connected directly with the seafaring world he later portrayed in the Ibis Trilogy. “I have encountered a maritime world that felt strikingly untouched by modern tourism yet deeply embedded in older histories of trade, migration and seafaring life.”

Before writing The Hungry Tide, Ghosh travelled extensively in the Sundarbans, a journey that profoundly shaped the novel’s sense of place. “Moving through its shifting waterways, remote islands and precarious settlements, I encountered a landscape where land is provisional, borders dissolve with the tide, and survival depends on an uneasy negotiation between humans, animals and water.” This instability becomes central to the novel, where travel is dictated not by human will but by tides, storms, cyclones and wildlife—most notably the Bengal tiger.

On research trips tied to Sea of Poppies and his non-fiction work on the opium trade, Ghosh has travelled to China, particularly Guangzhou, and Mauritius. There, he met descendants of Indian labourers and engaged deeply with local histories. “I encountered landscapes marked by historical rupture. The ports that once connected India and China through legal and illicit trade now stand as palimpsests of empire, memory and silence. My travels revealed how the violence of the opium economy—so central to British imperial power—has been unevenly remembered: deeply traumatic in China, often marginal in Indian and British narratives.”

More recently, Ghosh travelled to Mexico City. “It’s a city of 20 million people—a New Delhi-scale city. And yet it is so well managed. I have this theory that any city that is over 20 million will have a problem. You can go crazy being stuck for three hours in traffic. Somehow, it moves smoothly in Mexico City. People are friendly; there are these great museums, including the National Museum of Anthropology, where you can spend three full days.”

Brooklyn and Goa are the two places where Ghosh feels most at ease.

Amitav Ghosh, photographed in 1991 in Kolkata—then Calcutta—his birthplace and enduring emotional axis.

I have encountered a maritime world that felt strikingly untouched by modern tourism yet deeply embedded in older histories of trade, migration and seafaring life.

Amitav Ghosh

Author and Jnanpith Award Winner

The next frontiers

Ghosh hopes to explore Indonesia, Sub-Saharan Africa and South America more deeply. “In Indonesia, I am drawn by its cultural complexity and similarities to India, with its many worlds. I find Sub-Saharan Africa and South America compelling for their layered histories and connections to broader global narratives.”

A traveller's private rhythms

Exploring restaurants is not on his agenda, but tea certainly is. He loves a good Muscatel Okayti—a sweet, complex Darjeeling tea with muscatel grape undertones. “I am a Calcutta boy, after all; so, yes, I grew up drinking tea.” He also loves cooking, and spices appear insistently in his writing, particularly in Wild Fictions. “Turmeric is like a keystone spice. It’s good for your body because it fights inflammation; it has a wonderful colour, and it adds a special something to everything that you put it in.”

In Amitav Ghosh’s world, travel is never neutral. It carries memory, consequence and responsibility. And perhaps that is why his writing, which blends travel with economy, politics, and so much more, feels so urgently contemporary. At a time when the world is rethinking how—and whether—it should move, Ghosh reminds us that journeys have always mattered not for how far they take us, but for how deeply they bind us to the world we inhabit.

Guangzhou is part of the writer’s research into the opium trade and its long historical afterlives.